This long spell of fine weather has provided a cast iron excuse for lazing around and reading. It has always been the real purpose of holidays for me. In days of yore, when as a family we set off annually for a rural gîte, I ignored all protests and packed as many books into the boot as I could fit. I have a Kindle but for the absolute, indulgent luxury of reading, give me a hard back book every time.

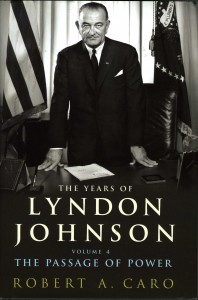

I have just completed Vol. 4 of Robert Caro’s massive Lyndon Johnson biography which runs to some 700 pages. It covers Johnson’s on/off bid for the Democratic nomination in 1960, the Kennedy assassination and his successor’s early days in the White House. The dramatic forces of the period are worthy of Shakespeare; it leaps into non-fiction’s most heady mainstream, with a true story of huge personalities, bloody assassinations, loves, hatreds and betrayals that renders it by turns gripping, sensational and deeply depressing. He spends a great deal of time on the chasm, filled with bitter dislike and distrust, between Johnson and the Kennedy forces, particularly Robert. Johnson displayed some of his worst personality traits towards them, his cruelty, political scheming and ultimately sycophancy. In turn, the Kennedys took savage delight in humiliating the Vice-President at every opportunity. Their enormous wealth and Harvard education gave them a social insouciance which contrasted with Johnson’s innate insecurity. He had received his education at the North Texas University for Teacher Training.

Caro does a superb job of discovering the real Johnson, the ambitious, sometimes ruthless politician, who also possessed a deep and sincere compassion for the dispossessed, “The Johnsons of Johnson City,” a compassion beaten into him by the sun and iron of his days working on the railroad tracks in the Hill Country of Texas, working alongside blacks, Mexicans, and the others left out of the American Experiment at that time. Kennedy, Roosevelt, and other icons of the American Left came to their liberalism through intellectual study; Johnson came to it through the blisters in his hands and teaching English to the children of Mexican immigrants in a run-down schoolhouse. Caro understands this uniqueness of Johnson in the political pantheon better than anybody, and this monumental work made me far better understand this most enigmatic and conflicted giant of the 20th Century.

The Kennedys had an appalling record on legislation; their bills were log-jammed in Congress and even by the time of the assassination, there was little prospect of them being enacted in federal law and, particularly so, in the case of the Civil Rights Bill which was loathed by the Southerners. The Kennedy dislike of Johnson was so intense that they could not accept the management of Congress advice from their Vice-President, whose control of the House as Majority Leader in the Fifties had been magisterial. Caro is superb in the detail of President Johnson’s expert handling of Harry Byrd, the old autocratic, patrician Virginian who had totally frustrated the Kennedy ambitions.

I recognised characters in the book whose identikit twins I had met in my own political career. My old union, the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS), has the right, designated by Royal Charter, to confer honorary degrees, Fellowships, on people that it has identified as having made a significant contribution to education in Scotland. For reasons that have more to do with petty jealousy than research, it has steadfastly ignored one of Scotland’s foremost educational thinkers simply because he was once a senior employee but left to work for the opposition, as they see it.

In 1967 I took some courses in the University of Delaware on a scholarship, funded by the Republic of Ireland. The ’68 election was looming, and Johnson, conscious of the importance of the Irish vote, met a group of us in the Rose Garden at the White House. He said very little; it was just another moment in the day of a gloomy President, trapped in an unpopular war in Vietnam which had been initiated by his predecessor. Separately at the Congress, we also met Robert Kennedy who showed his prescient understanding of the looming problems in the North when telling me, “I think Ulster will become Britain’s Vietnam.”

Within a few months , Johnson would announce his agonised decision not to seek re-election and Kennedy would be killed in the kitchens of a Los Angeles hotel.

Now John what a pity when you met Lyndon Johnston you did not have the opportunity to ask him about Precinct Box 13.(!948 Election.)

He used to keep a photograph of himself a few associates and Box 13 in his desk!

Thanks Brian

He wasn’t terribly communicative. I’m in Derry at the moment but I must look at Caro’s index on my return. He goes into minutiae